1.

Something has changed about the way my brain interfaces with the world, and I don’t think I’m alone.

I used to be able to read a book in one day, watch a whole movie without checking my phone, wind down in the evenings without thinking much about work or the world, and sleep deeply. I could move through the low-level hum of daily life without too much stress. But lately, my mind is scattered, my nervous system gnarly, and I feel more sensitive - fluorescent lights feel sharper, background noise more intrusive, the energy of crowds almost unbearable. Even watching a dramatic TV show in the evenings can leave me buzzing for hours. Was I masking this sensitivity all along, I sometimes wonder, or is this my mind on the internet?

2.

Recently, I was sitting next to my daughter in an airport. We were waiting to board a flight to Kefalonia, a paradise island and a perfect place to relax. She was on her iPad, and I was watching how she interacted with this device. Even though I’d carefully set up parental controls, limiting what she could access and for how long, I noticed how jaggedly she moved within this medium, switching from Disney, to Monument Valley, to a drawing app, then briefly to her Diary Of A Wimpy Kid book, before bouncing back to Disney.

As this attention-dividing scene unfolded, I felt something between recognition and grief. This restless attention-switching, I knew it intimately. But I also remembered going on holiday as a child, sitting in the back of the car ready for a 6-hour drive to Cornwall with one or two books. That was all. If I got bored, I’d stare out the window for a while then drift back to the book, because there was nowhere more exciting for my attention to go.

Spending time on a connected device is such a radically different experience. It feels like being a kid in a candy shop, surrounded by endless sugary highs and struggling to focus on any one. Surely, I thought, watching my daughter’s restless zig-zagging between stimuli, the internet is reshaping the way our minds work.

3.

My inspiration for this article was Michael Pollan’s brilliant book This Is Your Mind On Plants. In it, he argues that caffeine-producing plants haven't just given us a stimulating drink - they've colonised our consciousness so completely we've forgotten what baseline awareness even feels like. When he quit caffeine, it took three months of withdrawal, irritability, brain fog, and lost confidence before he returned to himself.

I was particularly curious about the idea that those caffeine-producing plants have been wildly successful from an evolutionary point of view. Their strategy: make humans dependent, and they'll cultivate you across the globe: “What the plant is doing, in effect, is manipulating the behaviour of animals for its own ends. The result is a kind of co-evolution: we changed the plant’s biology, and it changed ours."

But there was one point in the book I begged to differ. It was when Pollan described how giving up coffee for three months left him ‘sleeping like a teenager.’

Like a teenager?

I thought of how badly our teenagers are sleeping these days. And it’s not because of caffeine.12 Something else is manipulating our behaviour, interrupting our sleep, and colonising our consciousness in ways I believe are way more profound and harmful than the humble coffea arabica (coffee plant) ever could.

The internet has created an altered state of consciousness that's become our global baseline. Just as the caffeinated state became normalised, the digitally frayed mind has become our default frequency. It's affecting how we think, relate, work, rest, raise our children, reshaping the architecture of our inner lives without our consent, almost always without our fully noticing.

We are caught in a global nervous system hijack - an economy that doesn’t just sell us stuff, but quietly occupies our brains and bodies and starts rearranging the furniture, selling us back to ourselves, like a slightly glitchy version of who we used to be. This glitchy self is what Graham Music called The Buzz Trap: a state of chronic overstimulation, impulsive and restless, that mirrors traumatised states.3 And, just as caffeine provides the cure (wakefulness), for the problem it created (tiredness), so too do these ‘behavioural modification empires’ (as Jaron Lanier calls them) sell us solutions to the problems they created: they fray our nervous systems, then sell us meditation apps; they isolate us, then offer us likes and online ‘tribes’; they leave us overwhelmed, then numb us with endless distraction.

4.

So if like me you're feeling more sensitive, more scattered, more emotionally volatile these days, you’re not imagining it. Our nervous systems are being bent into new and gnarly shapes by a perfect storm of digital forces we are only barely beginning to understand.

Take sleep. Not the blue light everyone warns about - that's just the beginning. It's the buzz that follows us to bed. The drama, the compulsive checking, the dopamine grind. Our nervous systems stay wired long after the screen goes dark. We've normalised chronic sleep deprivation, this state now so widespread it seems unremarkable. Multiple studies have found, for example, that adolescents who use smartphones for more than two hours a day (isn’t that all of them/us?) are much more likely to experience sleep problems than those who don’t.45

When we lose sleep, we lose more than rest. The brain's ability to filter sensory input deteriorates, transforming everyday stimuli - the hum of traffic, the brightness of screens, the chatter of a café - into a neurological assault.6 So perhaps when we find ourselves becoming more irritable in crowds, more fragile after a long day, or unable to wind down, we’re not just ‘too sensitive’ or wired differently; we’re living in an overstimulated, under-rested state that our biology never evolved to handle.

5.

But sleep is just the beginning. Something stranger is happening in our ability to think.

With our 50 tabs and multiple apps open, we convince ourselves we are multitasking, but really we’re just rapidly switching, scattering attention, burning glucose, and leaving a trail of half-thoughts in our wake.

Our new baseline consciousness has been described as ‘continuous partial attention’: a constant skimming of surfaces, without ever sinking into depth. Studies show that frequent digital multitasking weakens our working memory, self-regulation, and cognitive flexibility.7 Even having a smartphone nearby, face-down, can drain cognitive resources, a quiet siphoning called ‘smartphone-induced brain drain’.8

Our brains are struggling to deal with the stuff of everyday life, because a portion of their resources is always elsewhere. Even when we’re not actively scrolling, our minds are craving the next ping, short clip, or dopamine hit. The more we’re conditioned into this state, the harder it becomes to tolerate slowness, uncertainty, or the unfinished.

Some neuroscientists call this a ‘cognitive control deficit’, our executive functions struggling to filter noise, delay gratification, or finish a thought. Children with higher screen time show more ADHD-like symptoms, and the relationship seems to go both ways: more screen time leads to more symptoms, and more symptoms lead to more screen time.91011 In one study of toddlers, every extra hour of daily screen time raised the risk of atypical, intense sensory reactions by 23%.12

I saw the seeds of this cognitive degradation watching my daughter fizzing around her iPad, unable to stick with one thing for more than a few minutes. And then I saw it in myself, reaching for my phone halfway through writing this sentence.

6.

It’s behavioural addiction by design, based on a powerful truth discovered by American psychologist B.F. Skinner in the 1950s. When the pigeons in his experiments were given food at random intervals (not every time they pecked a button, but just enough to keep hope alive) they began to peck compulsively. Intermittent rewards, it turned out, made for compulsive behaviour.

Now swap the pigeon for a human. The button for a screen. The pellet for a like, a ping, or a match. You get the idea.

Our devices are built on this logic. Intermittent reinforcement keeps us scrolling, checking, swiping, pecking. Not because every swipe delivers something good, but because sometimes it does. And our dopamine system is tuned not to certainty, but to maybe. We don’t get hooked on reward. We get hooked on the possibility of reward.

The more we engage, the more both systems adapt - the algorithms and our brains. Neuro-imaging studies show that excessive social media and smartphone use are associated with changes in the orbitofrontal and prefrontal cortices, regions responsible for decision-making, impulse control, and emotional regulation.13

Constant digital engagement leaves us feeling impulsive, restless, quick to frustration, easily bored, but hard to satisfy. Focus frays. Emotions feel louder. Boredom becomes unbearable. And when we try to unplug, we don’t feel calm, we feel twitchy. It’s withdrawal.

7.

With this level of addictive power, it is no wonder we spend more time on our devices than being present with other humans. Social deprivation is a real and pernicious effect, downstream of our digital compulsions.

Most of our digital interactions occur without eye contact, body language, or shared physical space. No breath, no pause, no awkward silences to stumble through. It’s connection without friction and friction, it turns out, is what builds social fluency. Social confidence is a muscle, and the best gym is real life.

Research shows that the more we rely on digital socialising over face-to-face contact, the more likely we are to experience social anxiety and discomfort in real-world settings.14 Our ‘social muscles’ atrophy. Eye contact feels intense. Small talk feels like work. Unpredictability, instead of being a normal part of human connection, starts to feel like a threat.

For children and teenagers, especially those already sensitive to sensory overload, this can spiral. A preference for text over talk. A need for rigid structure. Avoiding awkward moments turns into avoiding entire environments. School refusal and emotionally based school avoidance (EBSA) are now at record levels. As of summer 2024, the number of severely absent pupils in England has risen by 187% since before the pandemic, with nearly 1 in 3 parents reporting their child refused to go to school at least once in the past year.

School avoidance is complex, and certainly not just about digital worlds. In fact, for some autistic children, digital communication can feel safer, more manageable, less overwhelming than real-world interactions. But when screens become the primary social arena, real-world practice falls away. This can deepen avoidance, entrench anxiety, and reduce opportunities to develop flexible, spontaneous social skills. The good news is that interventions that pair reduced screen time with supported in-person connection have shown promising results, for children with ASD, including improvements in eye contact, emotional cue recognition, social confidence, and a reduction in parental stress.15 16

And here is cause for hope: our capacity for connection isn't lost, just under-rehearsed. In one study, children who spent just five days at an outdoor camp without digital devices showed significant improvements in reading nonverbal emotional cues and social fluency.17 When we step away from screens and back into embodied, face-to-face interaction, our nervous systems can recalibrate and our social confidence can return.

8.

Then there's what we might call the burnout of digital empathy. We've become bystanders to the terrors and horrors of all humanity. We aren’t built to witness the suffering of the entire world before breakfast. Yet many of us now scroll past war zones, burning forests, and emaciated children before we've even had our coffee.

Our nervous systems are increasingly plugged into a digital nervous system, a vast web pulsing with fear, outrage, and sorrow. Fight-or-flight sells.

Our bodies can't tell the difference between witnessing violence on a screen and witnessing it in person. The same stress hormones flood our systems whether we're watching a war zone from our couch or standing in one. Proximity to a disaster is no longer a solid predictor of psychological impact. Around 1 in 4 people report symptoms of secondary trauma from repeated exposure to distressing news and videos.18 Children and teens are particularly vulnerable.19

We consume more information in a single day than our ancestors did in a year. And much of it is painful. There’s no time to process, no village to help us hold it. And all we have to respond? A sad face emoji.😢

This leads to vicarious trauma, symptoms of which are just like the real thing, and include headaches, pervasive sadness, anger, helplessness, stomach aches, nausea, intrusive thoughts, hypervigilance, dissociation, fatigue, insomnia, and burnout.20 When we share a social identity or lived experience with those affected, the impact intensifies. Some researchers call this sociogenic transmission: when emotional states spread through social networks, shaping how entire groups feel and respond.21

I once worked with a Black British teenager in the aftermath of the George Floyd murder. Though she lived thousands of miles from Minneapolis, her body responded as if she had been there - nausea, insomnia, terror.

During COVID, another wave emerged. Some teens began experiencing tics after following influencers with Tourette’s on TikTok, a different example of how identification and repeated digital exposure can shape not just feelings, but behaviour and even neurology.22

We are not weak. We are sensitive beings trying to adapt to an overwhelming world. The problem isn’t our empathy, it’s the firehose of suffering with no outlet for repair.

9.

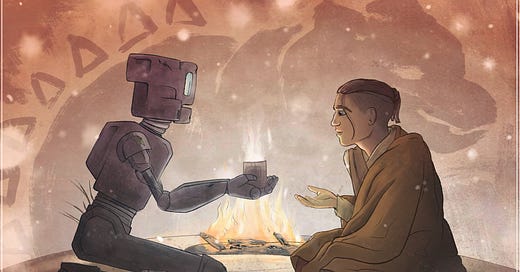

In the brilliant sci-fi book Psalm for the Wild-Built, a travelling tea-monk meets Mosscap, one of a group of awakened robots who became conscious and fled to the wilderness centuries ago. When the monk assumes the robots must all be networked together, Mosscap reacts with visceral horror:

"Would you want everybody else's thoughts in your head?"

Yet somehow, we humans have said yes to exactly that. We've become the networked beings that even fictional robots find repulsive. Billions of other people's thoughts, fears, appetites, all pulsing into our nervous systems via the same glass rectangles we cradle like prayer beads.

What's fascinating is how this altered state has become our new normal. Just as Pollan discovered that caffeine had become so normalised he'd forgotten what baseline felt like, we've mistaken our digitally-frayed consciousness for who we are. We accept as normal now to feel twitchy without our phones, normal to need constant stimulation, normal to sleep poorly and feel overwhelmed by everyday life.

Humans have of course always sought altered states - through plants, fungi, dance, meditation. But there's a profound difference between an ape discovering a mushroom that opens the doors of perception and having your consciousness colonised at industrial scale. One is exploration. The other, extraction.

That morning in the airport, as I observed my daughter's attention scatter across her screen, I was watching her mind being harvested, her dopamine, her neural pathways, all being shaped by algorithms designed for maximum extraction.

Later in Psalm for the Wild-Built, the awakened robot Mosscap speaks of ‘remnants’, old protective reflexes that no longer serve us. Robots have them in the form of old factory parts that still carry programming from before their awakening, a kind of ancient code that makes them flinch at things that no longer threaten them. "Remnants are powerful things," Mosscap says. "But if we choose to be, we're smarter than our remnants."

I like to think of my buzzing nervous system as one of those remnants. We don’t have to let ourselves be enslaved by this ancient code and those who prey on it. What I've learned, through my own stumbling attempts at resistance, is that awareness helps more than willpower. Noticing without judgment the compulsions: the itch when our phone's in another room, checking our apps like picking scabs. Accepting that we're addicted, that we're human animals responding predictably to engineered stimuli.

I wish I could say I've completely mastered this, but I haven't. I still lose evenings to the scroll. What works for me varies - sometimes app limits help, sometimes moving my phone to another room.

But the only consistent thing that seems to awaken me from my robotic trance is when I actively remember what matters most. The joy in my daughter's face when she knows I'm fully present with her. The total absorption of deep reading. Conversation that makes time disappear. When I recall these non-glitchy moments, how they feel, how much they matter to me, then I choose differently.

And maybe that's enough. Maybe the goal isn't to solve this permanently (we’re not all about to run off to the wilderness and become tea-monks, are we?), but simply to keep choosing. To keep remembering what consciousness feels like when it belongs to us again. A mind that knows how to rest. A self not scattered across ten tabs. A nervous system that pulses with presence, not notifications. A life returned to human scale.

https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/psychiatry/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2025.1548273/full

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1087079222001551

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/14753634.2014.916840

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7961071/

https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12889-022-14076-x?utm_source=chatgpt.com

https://www.mdpi.com/2227-9067/12/2/153

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26612392/

https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/full/10.1086/691462

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6176582/?utm_source=chatgpt.com

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24999762/

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30575870/

https://drexel.edu/news/archive/2024/January/Putting-Toddler-In-Front-of-TV-Atypical-Sensory

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8204720/#:~:text=Brain%20Imaging&text=Excessive%20smartphone%20users%20have%20shown,studies%20reviewed%20in%20this%20paper.

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S245195882100018X?via%3Dihub

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7670840/

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36348519/

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/265129715_Five_days_at_outdoor_education_camp_without_screens_improves_preteen_skills_with_nonverbal_emotion_cues

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/2167702619858300

https://www.sciencexcel.com/articles/1zkW1tq1N8VcWQHIY4CmKhm4YbDuJcqyVBdp1cJX.pdf

https://docs.rwu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1252&context=fcas_fp

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-023-33898-2

https://www.health.harvard.edu/blog/tics-and-tiktok-can-social-media-trigger-illness-202201182670

I couldn’t help notice the irony of my reading behaviour when engaging with your article. I was racing through, my mind scattered on a myriad of other things and it was a conscious effort to stay present with the text.

A health ‘scare’ has reconnected me with my body this week and I am endeavouring to choose that which I know sustains me - yoga, walking, reading. But it does feel an endeavour…an effort to resist the other pulls on my time and my energy.

Your words really resonated. Thank you.

Grateful for the meanderings of my own observations being brought into words so accurately by your reflections, Louis. Indeed we are far from alone in attempting to tease apart the complexities of overwhelming modernities, especially for our offspring and beyond. The hope is a dance emerges of digital usefulness with innovative guardrails to somehow infuse daily living with the ever shrinking ‘Ma’間( 🇯🇵 def: the moments between- no English word exists). The once long car rides, the pauses, the idle empty spaces so often undervalued. Thankfully, increased awareness is beginning to happen, your writing is part of that expansion. Paving new, improved pathways of balanced daily living we must remain optimistic for, although dauntingly ambitious.